|

Tipis are so media-associated with Native American Indians that they have become a stereotype (it's easy to draw their simplified forms, too). I was astounded to see, in a London-published, expensively-produced culture book for kids, a color photo of some friends putting up a colorful tipi at a Minneapolis powwow in 1978. "These Indians still live in teepees in the manner of their ancestors," the book explained. I laughed at first, then I started thinking of that expensive book, produced to sell classy historical and cultural ignorance to children, and it didn't seem so funny any more.

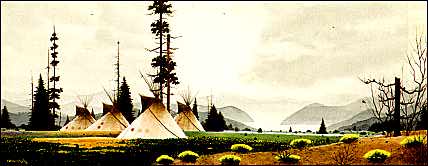

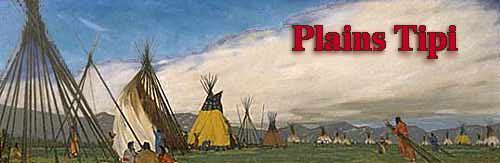

Canadian artist Peter White painted this 19th century Blackfoot encampment being set up. These large plains tipis were made of 15 - 50 buffalo hides, a style requiring the horse both to hunt that many buffalo and to drag the tipis on travoises, made of their own poles. The leftmost tipi is ready to have its cover pulled on. Just to the right of it, a tipi has been started with just the first 3 poles up and the hoist rope visible. Further right, two women pull a cover around and up onto the pole framework.

Luxton Museum: The tipi -- Quite a lot about tipis. There are study guide questions and off-line activities following this lesson, one of 20 about Plains culture prepared for Canada's SchoolNet with a large grant to the Luxton team from Industry Canada, a government agency. Be sure to click all the pictures and sidebars.

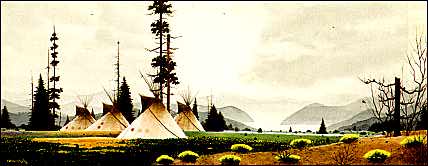

The Plains tipi is not shaped like a right-angle cone. It is sloped so it stands with its "back" to the prevailing wind direction, door on the opposite side. Navajo artist Clifford Brycelea -- to whom tipis, a Plains habitation, are exotics (Navajo traditional homes are hogans) -- paints a small Plains tipi encampment in the high country, in two seasons. In summer at dawn we see no smoke coming from these tipis yet, but we can see that the long sides slope to the left. The smoke flaps are open that way, too, to channel prevailing breezes on a hot night. Notice how the smoke flap control ropes wind around to the door, so the flaps can easily be moved during the night by those inside, if rain or storm comes up.

A similar encampment in winter shows a slight wind blowing against the long side (sloping to the left) of these snowbound tipis. Faint smoke from the last of an all-night banked fire is pulled out by this wind streamlining, which also minimizes heat loss due to wind on windier days than this one. We can see the smoke faintly, and see that the tipis' smoke flaps are now open to the right to protect against the wind blowing (gently) from the left. This controllable streamlining that pulls the smoke out from inside the tipi, makes it much more comfortable inside for people living there.

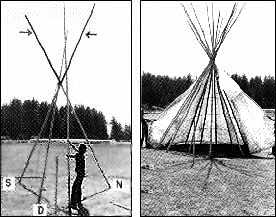

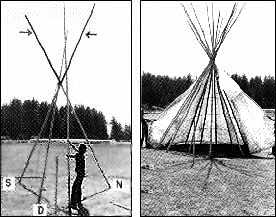

The tipi is set up by first bracing 3 poles against one another, then pulling the tripod of tall poles up by a rope hoist. These first or bracing poles are usually oriented to the compass directions (D, the door, is east) as shown here. When the rest of the poles have been positioned and lashed at the top, the tipi cover is pulled around the framework, as shown. The tipi is set up by first bracing 3 poles against one another, then pulling the tripod of tall poles up by a rope hoist. These first or bracing poles are usually oriented to the compass directions (D, the door, is east) as shown here. When the rest of the poles have been positioned and lashed at the top, the tipi cover is pulled around the framework, as shown.

Nomadics has been making and selling large canvas tipis since the early 1970's. Many seen at powwows and other Indian affairs were bought from Nomadics. Their website gives a great deal of info about the construction and furnishing of tipis (as well as their prices). Also for sale is the best book ever written or likely to be about the practical and historical Plains tipi, by Reginald and Gladys Laubin.

Symbolic meanings of parts of the tipi. Each of the 15 poles shown in this small tipi, and its other parts, serves as a way of traditional teaching about the important values and meanings of life. Great Plains Moccasin Factory, which is an aboriginal enterprise, explains the cultural teachings and meanings that this 15-pole tipi diagram indicates. (And. . . you also get a recipe for boiled skunk!) Not only do the tipi's parts serve as a teaching mnemonic, but the children, and later adults, who lived year-round in such tipis, felt literally surrounded by these meanings, they lived in them every day and night. Symbolic meanings of parts of the tipi. Each of the 15 poles shown in this small tipi, and its other parts, serves as a way of traditional teaching about the important values and meanings of life. Great Plains Moccasin Factory, which is an aboriginal enterprise, explains the cultural teachings and meanings that this 15-pole tipi diagram indicates. (And. . . you also get a recipe for boiled skunk!) Not only do the tipi's parts serve as a teaching mnemonic, but the children, and later adults, who lived year-round in such tipis, felt literally surrounded by these meanings, they lived in them every day and night.

Wikwemikong Tipi Co. -- Native tipi-making family from Wikwemikong Reserve, Manitoulin Island, Ontario. This style of tipi -- also canvas, and modeled on Nomadics' pattern -- is not originally part of Ojibwe or other Woodland tribal cultures. It is strictly an artifact of the horse-tipi buffalo culture of the great open plains. But though it is a stereotype, it has become symbolic to many Indian people, who spend considerable money on these status-and-culture symbols to take to powwows.

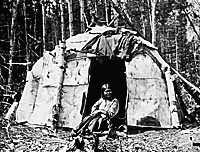

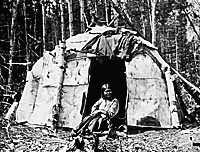

Before the coming of the horse, the plains were inhabited mainly by agricultural people living in river valleys. In the woodlands -- lake and forest land -- an older form of small, crude conical tipi was used in summers, and in an extended, shedlike version, to shelter the boiling kettles for spring maple sugaring. It's made of sheets of birch bark, insulated with many woven reed mats, all held in place by log bracers. This picture shows a couple of reservation police (they're wearing star badges) posing with their Minnesota Ojibwe family outside a birch bark tipi in 1905. By this time, these tipis were used only for summer camping. This type of bark tipi, and an equally small one made of hides, used all across the north on the tundra in summers, is not very comfortable, and not good winter protection. Before the coming of the horse, the plains were inhabited mainly by agricultural people living in river valleys. In the woodlands -- lake and forest land -- an older form of small, crude conical tipi was used in summers, and in an extended, shedlike version, to shelter the boiling kettles for spring maple sugaring. It's made of sheets of birch bark, insulated with many woven reed mats, all held in place by log bracers. This picture shows a couple of reservation police (they're wearing star badges) posing with their Minnesota Ojibwe family outside a birch bark tipi in 1905. By this time, these tipis were used only for summer camping. This type of bark tipi, and an equally small one made of hides, used all across the north on the tundra in summers, is not very comfortable, and not good winter protection.

The small bark tipi evolved from the earlier dome-shaped birch-bark wigwam of woodland people. These are individual nuclear family homes. They are easier to insulate in winter. than the conical small tipi shape. In addition to the woven reed mats, wigwams were covered in winter with a thick layer of dirt and sod, braced up around the sides and over the roof, after the danger of late fall rains was past. These structures are small. Most cooking was done outside (there was a very small heating fire centrally within). They were built anew each season at each camping place, with fresh birchbark and new matting insulation. These were shelters for sleeping, and to wait out the storms. By contrast, the Plains buffalo hide tipi, with its large diameter, its high and controllable smoke exit, a design permitting a larger inside fire, was a roomy, yet cosy place. The wigwam's dome construction might be of bent willow, or flexible, tough dogwood, often called "red willow" and considered one of the 4 Anishinaabe sacred plants. The small bark tipi evolved from the earlier dome-shaped birch-bark wigwam of woodland people. These are individual nuclear family homes. They are easier to insulate in winter. than the conical small tipi shape. In addition to the woven reed mats, wigwams were covered in winter with a thick layer of dirt and sod, braced up around the sides and over the roof, after the danger of late fall rains was past. These structures are small. Most cooking was done outside (there was a very small heating fire centrally within). They were built anew each season at each camping place, with fresh birchbark and new matting insulation. These were shelters for sleeping, and to wait out the storms. By contrast, the Plains buffalo hide tipi, with its large diameter, its high and controllable smoke exit, a design permitting a larger inside fire, was a roomy, yet cosy place. The wigwam's dome construction might be of bent willow, or flexible, tough dogwood, often called "red willow" and considered one of the 4 Anishinaabe sacred plants.

This colored engraving shows a wigwam frame being lashed together, while behind it, a woman puts some final touches on the birchbark outer cover that tops insulation of woven reed mats. The engraving is said to depict Algonquian people, but whether the Canadian tribe of that name or any of the Eastern Woodlanders whose language group is Algonquian, who used this form of housing in pre-contact times, is not told. A similar type of frame is used today -- covered with canvas and blankets -- for sweat lodges. This colored engraving shows a wigwam frame being lashed together, while behind it, a woman puts some final touches on the birchbark outer cover that tops insulation of woven reed mats. The engraving is said to depict Algonquian people, but whether the Canadian tribe of that name or any of the Eastern Woodlanders whose language group is Algonquian, who used this form of housing in pre-contact times, is not told. A similar type of frame is used today -- covered with canvas and blankets -- for sweat lodges.

This photo taken on the Montana Blackfeet (Southern Pikunni, Piegan) reservation shows a tipi and a dome-shaped sweat lodge isolated from the lone house. The tipi is used by those preparing for a sweat, waiting a turn and sometimes when people haven't prepared a sweat, the family will just sit in their tipi and sing. Ken Blackbird (Assiniboine) took this photo. The little grove and clearing, some distance from the lonely house among the rolling hills, looks to my city eyes like an ideal location. So, considering the importance of that little clearing to the family there, people do still live in tipis, though not quite the way that foolish children's book meant. What's lived there in that little clearing is spiritual life. It takes a long time to prepare for a sweat, heating the rocks, so it's done mostly on weekends and holidays. People sometimes come from other places for this life.

This photo taken on the Montana Blackfeet (Southern Pikunni, Piegan) reservation shows a tipi and a dome-shaped sweat lodge isolated from the lone house. The tipi is used by those preparing for a sweat, waiting a turn and sometimes when people haven't prepared a sweat, the family will just sit in their tipi and sing. Ken Blackbird (Assiniboine) took this photo. The little grove and clearing, some distance from the lonely house among the rolling hills, looks to my city eyes like an ideal location. So, considering the importance of that little clearing to the family there, people do still live in tipis, though not quite the way that foolish children's book meant. What's lived there in that little clearing is spiritual life. It takes a long time to prepare for a sweat, heating the rocks, so it's done mostly on weekends and holidays. People sometimes come from other places for this life.

This life is lived, rather than as an object, merely inhabited. The tipi and sweat lodge are part of it, here, but they are also signs: it can be lived other ways, too.

Continue -- Pueblos Continue -- Pueblos

|

The tipi is set up by first bracing 3 poles against one another, then pulling the tripod of tall poles up by a rope hoist. These first or bracing poles are usually oriented to the compass directions (D, the door, is east) as shown here. When the rest of the poles have been positioned and lashed at the top, the tipi cover is pulled around the framework, as shown.

The tipi is set up by first bracing 3 poles against one another, then pulling the tripod of tall poles up by a rope hoist. These first or bracing poles are usually oriented to the compass directions (D, the door, is east) as shown here. When the rest of the poles have been positioned and lashed at the top, the tipi cover is pulled around the framework, as shown.

Before the coming of the horse, the plains were inhabited mainly by agricultural people living in river valleys. In the woodlands -- lake and forest land -- an older form of small, crude conical tipi was used in summers, and in an extended, shedlike version, to shelter the boiling kettles for spring maple sugaring. It's made of sheets of birch bark, insulated with many woven reed mats, all held in place by log bracers. This picture shows a couple of reservation police (they're wearing star badges) posing with their Minnesota Ojibwe family outside a birch bark tipi in 1905. By this time, these tipis were used only for summer camping. This type of bark tipi, and an equally small one made of hides, used all across the north on the tundra in summers, is not very comfortable, and not good winter protection.

Before the coming of the horse, the plains were inhabited mainly by agricultural people living in river valleys. In the woodlands -- lake and forest land -- an older form of small, crude conical tipi was used in summers, and in an extended, shedlike version, to shelter the boiling kettles for spring maple sugaring. It's made of sheets of birch bark, insulated with many woven reed mats, all held in place by log bracers. This picture shows a couple of reservation police (they're wearing star badges) posing with their Minnesota Ojibwe family outside a birch bark tipi in 1905. By this time, these tipis were used only for summer camping. This type of bark tipi, and an equally small one made of hides, used all across the north on the tundra in summers, is not very comfortable, and not good winter protection. The small bark tipi evolved from the earlier dome-shaped birch-bark wigwam of woodland people. These are individual nuclear family homes. They are easier to insulate in winter. than the conical small tipi shape. In addition to the woven reed mats, wigwams were covered in winter with a thick layer of dirt and sod, braced up around the sides and over the roof, after the danger of late fall rains was past. These structures are small. Most cooking was done outside (there was a very small heating fire centrally within). They were built anew each season at each camping place, with fresh birchbark and new matting insulation. These were shelters for sleeping, and to wait out the storms. By contrast, the Plains buffalo hide tipi, with its large diameter, its high and controllable smoke exit, a design permitting a larger inside fire, was a roomy, yet cosy place. The wigwam's dome construction might be of bent willow, or flexible, tough dogwood, often called "red willow" and considered one of the 4 Anishinaabe sacred plants.

The small bark tipi evolved from the earlier dome-shaped birch-bark wigwam of woodland people. These are individual nuclear family homes. They are easier to insulate in winter. than the conical small tipi shape. In addition to the woven reed mats, wigwams were covered in winter with a thick layer of dirt and sod, braced up around the sides and over the roof, after the danger of late fall rains was past. These structures are small. Most cooking was done outside (there was a very small heating fire centrally within). They were built anew each season at each camping place, with fresh birchbark and new matting insulation. These were shelters for sleeping, and to wait out the storms. By contrast, the Plains buffalo hide tipi, with its large diameter, its high and controllable smoke exit, a design permitting a larger inside fire, was a roomy, yet cosy place. The wigwam's dome construction might be of bent willow, or flexible, tough dogwood, often called "red willow" and considered one of the 4 Anishinaabe sacred plants. This colored engraving shows a wigwam frame being lashed together, while behind it, a woman puts some final touches on the birchbark outer cover that tops insulation of woven reed mats. The engraving is said to depict Algonquian people, but whether the Canadian tribe of that name or any of the Eastern Woodlanders whose language group is Algonquian, who used this form of housing in pre-contact times, is not told. A similar type of frame is used today -- covered with canvas and blankets -- for sweat lodges.

This colored engraving shows a wigwam frame being lashed together, while behind it, a woman puts some final touches on the birchbark outer cover that tops insulation of woven reed mats. The engraving is said to depict Algonquian people, but whether the Canadian tribe of that name or any of the Eastern Woodlanders whose language group is Algonquian, who used this form of housing in pre-contact times, is not told. A similar type of frame is used today -- covered with canvas and blankets -- for sweat lodges. This photo taken on the Montana Blackfeet (Southern Pikunni, Piegan) reservation shows a tipi and a dome-shaped sweat lodge isolated from the lone house. The tipi is used by those preparing for a sweat, waiting a turn and sometimes when people haven't prepared a sweat, the family will just sit in their tipi and sing. Ken Blackbird (Assiniboine) took this photo. The little grove and clearing, some distance from the lonely house among the rolling hills, looks to my city eyes like an ideal location. So, considering the importance of that little clearing to the family there, people do still live in tipis, though not quite the way that foolish children's book meant. What's lived there in that little clearing is spiritual life. It takes a long time to prepare for a sweat, heating the rocks, so it's done mostly on weekends and holidays. People sometimes come from other places for this life.

This photo taken on the Montana Blackfeet (Southern Pikunni, Piegan) reservation shows a tipi and a dome-shaped sweat lodge isolated from the lone house. The tipi is used by those preparing for a sweat, waiting a turn and sometimes when people haven't prepared a sweat, the family will just sit in their tipi and sing. Ken Blackbird (Assiniboine) took this photo. The little grove and clearing, some distance from the lonely house among the rolling hills, looks to my city eyes like an ideal location. So, considering the importance of that little clearing to the family there, people do still live in tipis, though not quite the way that foolish children's book meant. What's lived there in that little clearing is spiritual life. It takes a long time to prepare for a sweat, heating the rocks, so it's done mostly on weekends and holidays. People sometimes come from other places for this life.