Elsie Allen grew up speaking no English, raised by her grandmother in the Cloverdale area north of Lake Mendocino, northern California. At 11 she was captured by authorities and taken away to attend a distant boarding school. Pomo experiences and attitudes of everyone toward this forced separation were the same as for all other Indian people: "My mother used to hide me whenever the white people came because we had heard of Indian children who had been kidnapped. My great-grandmother said that when she was young, a number of Indian children were brought down from the north by whites riding on mules. Her aunt fed about 7 or 8 of these small children, who were being carried south to be sold to ranchers. They were so starved, they swallowed their food whole. My people wept when these children wre taken away." | |

|---|---|

|

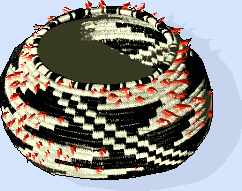

Nellie Burke, Elsie's grandmother taught her a great deal about plants and basketry before she was taken away to Covelo Indian boarding school when she was 11. She was photographed in 1898. This looks like a world-beater basket for size she's making -- at least 4' in diameter -- a twined storage basket that must have taken several years for her to make. It was completed in 1898. |

Annie Burke, Elsie's mother, photographed in 1935, is teaching an unidentified young Pomo girl to weave. 25 years later, Annie Burke was photographed with great-great grandchildren -- and this photo was in the background, as if to show basketry passing to new generations. Elsie worked at farm labor, as a domestic, and as a laundress, to support her family. She could weave only a little, and was not free to gather plants, mostly all some distance away. |

|

| "In the first few years of my married life, I attempted basket-weaving. I made a basket that was buried with my grandmother. My next basket was buried with my great-uncle. A third basket was passed all around to relatives when someone died [holding honor gifts] and finally somehow came back to us and was buried with my brother-in-law. I didn't have a good feeling about making baskets after that. Mother told me she did not want this to happen to her, [traditionally a Pomo woman's baskets and tools and supplies were all buried with her]. as she wanted me to have her baskets to help me when I started up basketweaving again. Mother died in 1962, and I have tried to keep my promise."

In her book, Elsie says nothing about her political activity and help on the behalf of Pomo people. Her mother told her (as she later said on a videotape) that the baskets should be used to take Elsie travelling, where she could use them to show white people that the Pomo Indians "weren't dumb."

Elsie had been active in the Ukiah-based Pomo women's self-help club. She was on its basketry committee in the 1940's and 50's. During this period, the women's group raised money -- by basket sales and many other ways -- for Native college scholarships, assistance to distressed Pomo people, and to finance an important lawsuit. In the racist areas of Mendocino County and Sonoma County, Pomo people's imememorial land, where most still live on a number of tiny, scattered federal reservations, Steven Knight, married to a Pomo woman, tried to enter his daughter into the local public school. The public schools would not admit Indian children, who were captured and sent off to distant BIA boarding schools. In 1923, Knight undertook a lawsuit on behalf of his daughter. There was an out-of-court settlement (to avoid setting a precedent) that allowed her to enter the local public school -- but the school board didn't allow other Pomo kids in. Local businesses were highly discriminatory, with signs "No dogs or Indians allowed" common. Restaurants wouldn't serve Indians; they were not allowed in local churches. An intense irritation to the people was the Ukiah movie theatre, which forced Indian ticket-holders to sit on a back balcony, rather than on the main floor, with whites. In the late 1940's Steven Knight, with financing from the women's group, filed a second lawsuit, this time on behalf of his granddaughter, because of the theater's discrimination against Indian people. This (when finally won) forced many other local businesses to stop their more open discrimination, for fear of being sued. The school board, however, exercised a legal option to operate a "separate but equal" little public school for Indian students until 1932. When Elsie wrote, in 1972, that "Unfortunately some of my Pomo people were not pleased with me," for keeping her mother's baskets and beginning to teach weaving to others than members of her immediate family, it was really fear and the climate of the "termination times" rather than cultural traditions that lay behind it. All tiny Pomo reservations (among a total of 41 "rancherias" -- Indian reservations in California) were terminated from federal status in 1958. In 1976, the Coyote Valley Pomo Band, whose resrvation had been forcibly drowned by Coyote Valley Dam, sued successfully to reverse their terminated status in Eddie Knight et al vs. U.S. Eventually the court ruled their termination and the land-taking were invalid. This didn't get their land back, but they purchased 58 acres in Redwood Valley that has federal reservation status now for Coyote Valley Band. But in 1962, when Elsie took up her heritage, the people were despirited, discouraged. "They [conservative, assimilationist Pomo people] felt these old ways should die and we should forget the past heritage," Elsie wrote. "Perhaps they thought people would laugh at us for taking up things our ancestors once did. Even one white gentleman came to me and told me I should not do it because it would destroy a lot of plants." Of course, this was really about racism (and Native fear of it), but then there's quite a tradition of that in California. | |

| This photo, showing Elsie Allen holding a practical willow baby carrier-swing she made (and gives detailed instructions for making in her book) was taken by Robert Cooper around 1971. It shows her -- in her early 70's -- as a strong woman with a committment through her art (and life) to the future. At the time her book was published, in 1972, there had been considerable Indian activism in California, but this did not translate into enlistment by Indian youth in cultural activities -- of which most of the militant youth were ignorant. |  |

The occupation of the abandoned California prison island, Alcatraz, by Indians of All Tribes began in 1969, forced eviction was in 1971. (Here's a fairly even-handed National Park Service version.) In 1970, dozens of abandoned government sites in California were occupied claiming the abandoned land for Indian universities, cultural centers, and the like. Pomo youth were involved in some occupations, especially ionvolving the 1960 drowning of the Coyote Canyon Band's land under a dam, and the U.S. federal termination of all Pomo bands in 1958. Several specifically Pomo actions took place in 1970. A surplus abandoned Army radio transmitter base, near the Pomo Middletown rancheria in Lake County was occupied in May 1970. The Pomo hopeed to reclaim the 640 acre site to make up for the 100 acre of Middletown that were lost in termination, but they were evicted by brutal deputies, and 12 people were convicted for it in August. A few days after the arrests from the Middletown Army base, another Pomo group occupied (re-occupied) 64-acre Mu-Do-N Island (aka Rattlesnake Island) which is right off the point of their tiny then-terminated rancheria on the east side of Clear Lake. This is an ancient burial ground and old village sacred site, and the location of many needed plants. Boise Cascade Lumber company simply took this land, and barred Indians from ceremonial and plant-gathering access. They were about to erect a condo on the old cemetery. (Rattlesnake Island is presently for sale, and the El-Em/ Sulphur Bank Band is trying to find a way to acquire it.) In 1970, those involved were arrested (some were severely beaten) and there were more convictions. In November of 1970, about 24 Pomo (and other) activists occupied an abandoned CIA spy post near Santa Rosa. Used in the 1950's to monitor foreign broadcasts, it had been vacant for a decade. They were forcibly removed 3 days later with 5 arrests. Ultimately, though, title to this land was transferred to the Pomo (intertribal). It is now the Ya-Ka-Ama ("Our Land," in Pomo) American Indian Learning Center, just as had been demanded in 1970. It maintains a nursery for endangered and other Native plants, carries out related economic development projects, and educational and cultural programs, supported and participated in by all the Pomo bands. As can be imagined, this challenge to the U.S. military and to its covert political repression agency the CIA produced immediate heavy government responses. Non-participating Pomo were regarded with even more racism and suspicion, and there were government harassments, family visitations, investigations, firings. Elsie and the few elders who were making fine baskets, sold them to raise money for lawyers, somewhat more effective (moneywise) than the group of Kashaya Pomo who in Novmber, 1970, collected just $22 in tolls from motorists crossing the (then-terminated) Pomo reservation at Stewart's Point. Another group of young Pomo (assisted by Alcatraz Mohawk leader Richard Oakes) charged $1 toll on the Skaggs Springs road. They were indited for felony robbery and obstructing a public roadway. The net result was some short-lived publicity -- and more need for legal help and money. The orientation of most youthful Native liberation leaders was political, focused on land, sovereignty, rights. There were vast demands on time and limited resources for the activists. There was little sustained attention to cultural heritages, especially not for a difficult, time-consuming and highly-demanding art like basketry. At the same time, many older Pomo people (though not Elsie) feared white backlash from this new militancy, even beyond the arrests and local law enforcement harassments. They expressed an assimilationist, quietist viewpoint: Keep your head down. Thus in 1972, in her book, Elsie expresses disappointment at the results of her attempts to teach the art and craft, although her basketry classes were well-attended by white women. This -- and growing attention from universities -- actually did help to create a more positive climate for California Indian people. But it still disappointed her. "I didn't attract many Indian girls, as they didn't like to dig in the mud. I am happy to teach all, and would be especially happy if some local Indian girls would become interested in learning this art. Basket weaving needs dedication and interest and increasing skill and knowledge. It needs feeling and love and honor for the great weavers of the past who showed us the way. If you can rouse in yourself this interest, feeling and dedication, you also can create matchless beauty and help renew something that should never be lost." | |

|

Elsie found a true apprentice to study the art with her, and to carry it on, and to teach others. This photo shows Elsie at her home in 1980, with her grand-niece, Susie Billy holding the start of a basket at the right. |

"My grandmother was a very fine weaver. We had a number of her baskets when I was growing up. I would ask my father 'What are the materials? How were they started? How did she do this?' and he would always tell me 'Someday we can go back to our people and maybe there'll be someone that can teach you there.' "When I appeared at my great-aunt's [Elsie Allen's] doorstep and told her I was interested in learning the weaving, she said 'I started a class yesterday and no one came. The next class is tomorrow, so you can come and it will really be the first class.' " Susie studied with Elsie for 5 years, every day. She realized "I couldn't separate it from the traditions, the customs, religion, their whole life-style. All these things went together, you couldn't learn just one part. Elsie held out her hand and handed me this awl, this knife. She said 'They were your grandmother's, I wanted to give them to you.' " | |

| "At that moment I had like this magic given to me, my grandmother's spirit was passed on to me. I realized it was actually a spiritual path for me, which was a complete surprise, because it had never occurred to me. Through basketry, I feel I have made connections with something very ancient within myself and from my people." (Photo: Susie in 1991 at the New York Heye-Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian.) |  |

Elsie remembered how it was: "We would fast before starting on a red feather or woodpecker feather basket. We would work at it as long as possible, then when we were too hungry, we would eat but no longer work on the basket. The fasting was for purification, so as to receive help from the Great Spirit for whatever we did."  | |

| Tillie Hardwick, a Pinoleville Pomo, sued the U.S. in the early 1980's on the behalf of the terminated Pomo reservations. Victory restored federal status to 17 small California reservations, including many -- but not all-- Pomo bands, which continue their struggle for federal recognition. Today, Susan Billy teaches, writes, makes baskets and jewelry and owns a bead store in Ukiah, the town where, not long ago, store-window signs saying "No dogs or Indians allowed in here" were common. The people -- and the tradition of fine basketry -- continue. Not without struggle, though; it's not easy. | |